Founding a Humanities Institute: The Case of the Alexander Grass Humanities Institute at Johns Hopkins University

By William Egginton, Director and Decker Professor in the Humanities

About five years ago, when I was serving as vice-dean for graduate education in the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences at Johns Hopkins, at the top of our list of challenges was addressing the tilt in admissions and student interest toward STEM fields and away from the humanities. While this was and is a national trend, and although our own longitudinal analysis did not indicate the same decline in majors and enrollments in humanities courses that was being reported nationally, we felt that Hopkins’ reputation as a school primarily for premeds and engineers had an iniquitous effect on the overall campus experience for all students.

This effect could be felt in numerous ways. For students in the sciences it contributed to the experience of overcrowded classrooms and cutthroat competitiveness that had helped make Hopkins one of those schools “where fun goes to die.” Humanities students, who in stark contrast to their STEM-oriented peers reported sky-high satisfaction rates in their courses, often found themselves socially adrift, without a robust community of fellows with shared interests, and at times even belittled by their scientific colleagues in more or less covert cases of what has come to be known as “humanities shaming.”

The reputation was also harmful at the level of admissions, yield, and class formation. Admissions regularly reported to us that in order to balance our entering classes and admit, as well as yield, even a relatively respectable fraction of students interested in the humanities, they would have to go quite a bit further “down the list” in terms of those metrics that were and are counted in the all-important annual rankings. As much as the faculty would rail against our policies and admissions being guided by the questionable methodologies of U.S. News and World Report’s artificial and one-dimensional rat race, the upper administration held gaining and holding a position in that index’s top ten as a consistent goal, and there was little we could do about it. What resulted was a classic catch-22: by conforming to the pressures of one index, average SAT scores and GPA of the admitted class, we were slipping in another, student satisfaction—along with, implicitly, the balance of fields that any great university should aspire to.

While changing admissions criteria was outside the bailiwick of the vice deans and faculty considering such questions, curricular decisions were not, and so a group of faculty embarked on a number of initiatives intended to increase the profile and ultimately the draw of humanities courses and majors at Hopkins. The reasoning was that if more families and students learn over time to associate the school with what is and always has been, in fact, the extraordinary quality of its faculty and programs in the humanities, more students would be drawn to apply, and that this would initiate a virtuous cycle whereby more students of a higher achievement level could be admitted, eventually yielded, and finally in turn create the very milieu that would reproduce Hopkins as a destination as much for the humanistic as for the STEM-minded.

Of the several multi-pronged approaches we adopted, I was closely involved in two. The first chronologically-speaking was the creation of a new major, Medicine, Science, and the Humanities, intended both to take advantage of a niche tendency among many of our humanists to harbor interests in the sciences and include those interests in their work and teaching, as well as to provide a platform for those students who are among the upwards of 60 percent of Hopkins students who complete the premed track and who might also wish to major in the humanities, but who are dissuaded by fear, family disapproval, or simply lack of programmatic opportunity from doing so—and this despite obvious, loud, and growing indications from medical schools that they were and are looking for humanities majors!

The second plan, which would take a bit longer to put into action, was to create a humanities institute, whose goals would be to focus attention on the great work already being done by our faculty in the humanities, support humanities research, teaching, and cross-disciplinary conversations, and create a venue for community outreach and the promotion of public humanities.

To this end we began by researching the state of humanities centers and institutes among our peer institutions. We recognized that our own situation was complicated because Hopkins had, since 1966, had an academic department called the Humanities Center. We quickly determined what most of us already realized, however: the Hopkins Humanities Center had little in common with its namesakes at any of the other institutions we were using as benchmarks. Those centers or institutes tended not to be degree-granting, ours was; theirs tended not to have core faculty; ours did; theirs tended to host conferences and events, internal fellows, and at times external fellows, from the wide spectrum of fields and interests comprising the humanities; ours was a tiny, highly regarded department of critical theory, whose own appropriate benchmarks were departments like Duke’s Program in Literature, Chicago’s Committee on Social Thought, or Santa Cruz’s History of Consciousness. Our other finding was dispositive: we were the only university among our peer group with no actual functioning humanities center.

The next step was to begin to think about what a humanities center or institute at Hopkins should look like. To that end the dean’s office asked a distinguished professor of Italian and Classics to lead a series of conversations with faculty around the desirability for such an institute and how it should be structured. Data from these conversations was ultimately handed over to a faculty working group, which in turn designed a blueprint. While the blueprint is too technical and involved to delve into here, some important points were: we decided not to adopt a common practice whereby the institute’s programming would adhere to an annual theme, instead preferring to recognize, amplify, and support existing work and faculty interests; we identified three broad areas or “vectors” that the Institute would focus on, specifically, aesthetics, media and knowledge, and public humanities; and we included a graduate fellows program as being something that would need to be a part of the Institute from the ground floor.

At this point the blueprint was given to the development team, which began to work with potential donors. One donor who had endowed chairs for the medical school had recently had a child attend Krieger School of Arts & Sciences (KSAS) at Hopkins and major in the humanities and turned out to be very enthusiastic about the naming opportunity for a brand-new humanities institute at Hopkins. She read the blueprint and very soon thereafter committed the money needed to endow the institute. Since it often takes several years for large gifts to be completed and start paying out, another donor with deep ties to the humanities at Hopkins stepped up with a shorter-term current use gift, which allowed us to begin programming right away. In the fall of 2016, only a few years after we had begun discussing the idea of a humanities institute at Hopkins, the Alexander Grass Humanities Institute (AGHI) celebrated its founding with an inaugural conference.

As of this writing AGHI has just finished its third year in existence, and already the Institute, which I have now started to hear pronounced as “Aggie” in conversations on campus, has become a fixture at the heart of Hopkins’ intellectual life. While the individual initiatives and events we have spearheaded, coordinated, or supported are too numerous to list here, a few standouts are worth mentioning.

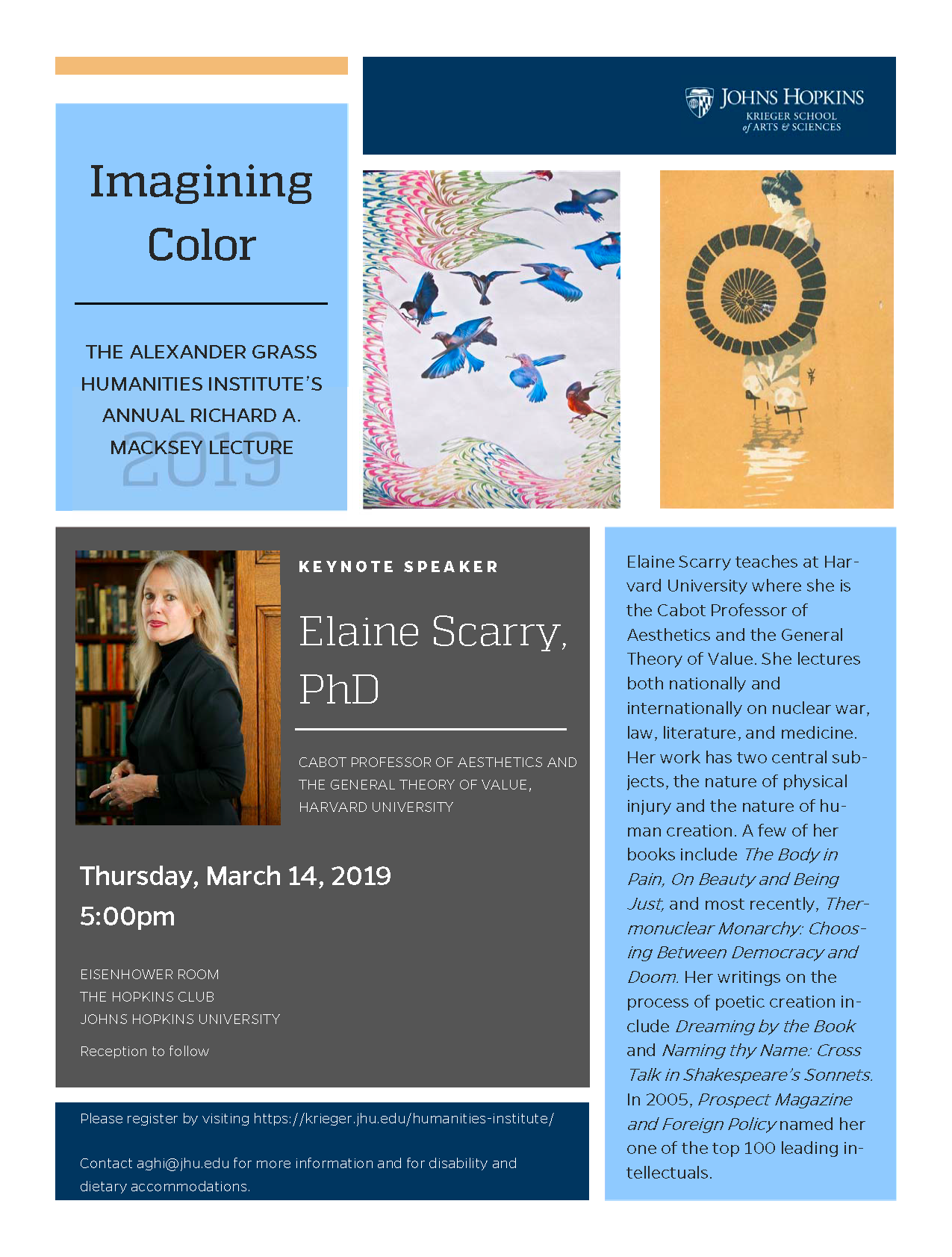

Early in the life of the Institute the donor who had come up with the current use gift, an alumnus who had studied with the legendary literary scholar Richard Macksey, asked if we would consider naming an event in his honor. The faculty advisory board (which consists of at least one representative from each of the humanities and humanistically-oriented social science departments, as well as from the libraries and several related centers and programs) unanimously decided to create an annual lecture named in his honor. As a result, each year in March we host the Richard A. Macksey lecture, delivered by a prominent scholar in the humanities on a topic of wide interest to faculty and students. This year, for example, the lecture was given by Harvard Professor of English Elaine Scarry. While there are often lectures in a given field that transcend the more parochial interests of a given department’s faculty, there had never been a regularly-schedule annual lecture in the humanities that fit that description. After three years the annual Macksey lecture has established itself as an intellectual happening of a certain stature and significance of which the university community is aware and looks forward to each year.

Early in the life of the Institute the donor who had come up with the current use gift, an alumnus who had studied with the legendary literary scholar Richard Macksey, asked if we would consider naming an event in his honor. The faculty advisory board (which consists of at least one representative from each of the humanities and humanistically-oriented social science departments, as well as from the libraries and several related centers and programs) unanimously decided to create an annual lecture named in his honor. As a result, each year in March we host the Richard A. Macksey lecture, delivered by a prominent scholar in the humanities on a topic of wide interest to faculty and students. This year, for example, the lecture was given by Harvard Professor of English Elaine Scarry. While there are often lectures in a given field that transcend the more parochial interests of a given department’s faculty, there had never been a regularly-schedule annual lecture in the humanities that fit that description. After three years the annual Macksey lecture has established itself as an intellectual happening of a certain stature and significance of which the university community is aware and looks forward to each year.

Another area where we’ve made concerted inroads is in the questions of coordinating and communicating about the plethora, one might even say superabundance, of humanities-related events that take place daily on campus, often conflicting with one another to the chagrin of organizers and attendees alike. While we have yet to completely solve the problem, the introduction in our first year of the weekly “This Week in the Humanities” flier is starting to push the needle. More and more I am getting the sense from colleagues that the flier—which appears each Saturday and lists in an easily parsed, colorful format the entirety of the week’s events by day and time—is becoming the go-to means of knowing what is happening and when. A remaining challenge is to accustom faculty and administrators to consulting our centralized calendar when organizing events in order to minimize scheduling conflicts, and also to convince administrators to give up the practice of also distributing individual event notices as email attachments. The latter, which at this point practically no one opens, still clatter around in our inboxes to the tune of several dozen a week.

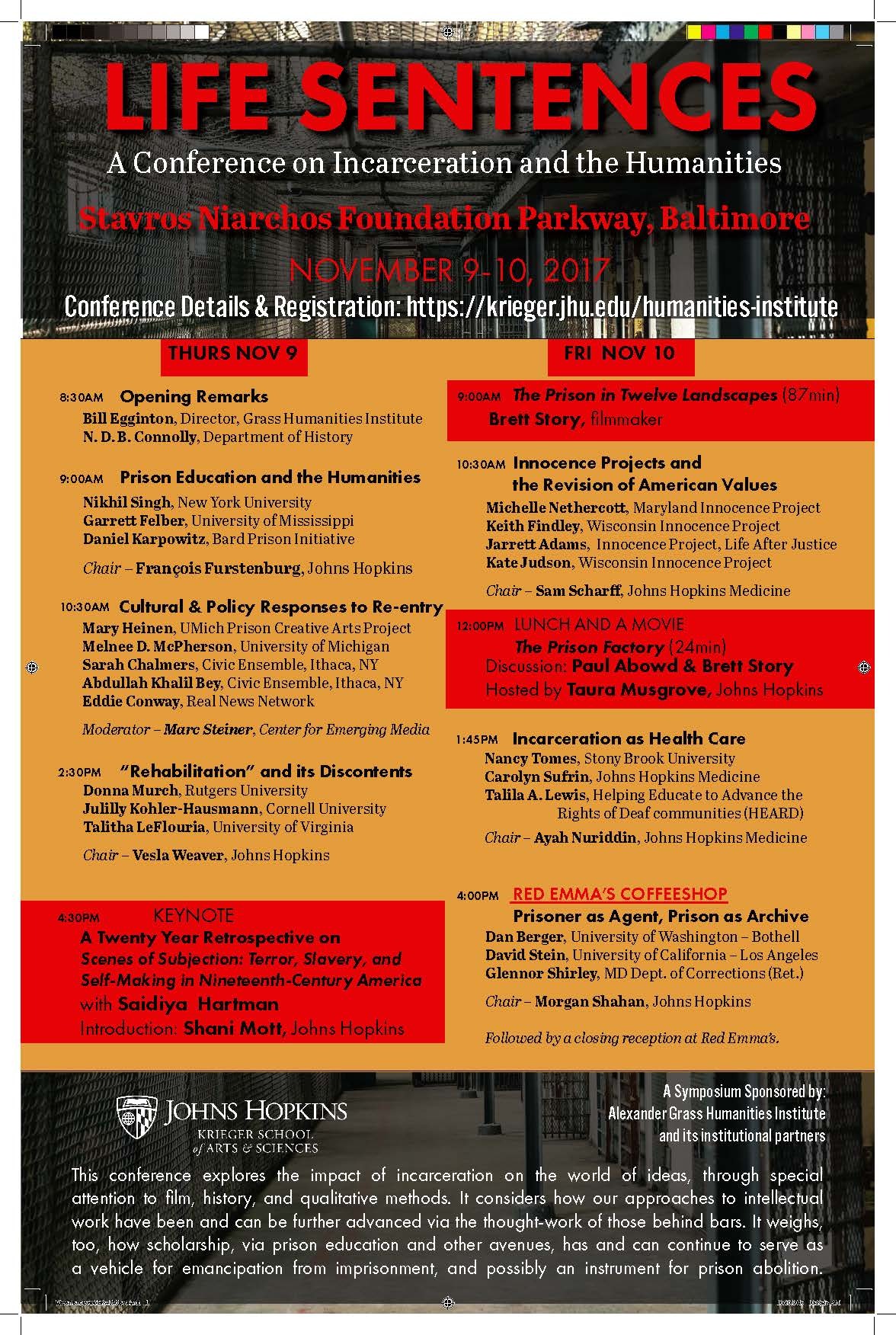

As the public humanities was one of the founding missions of the Institute we’ve made a point to cast our distribution network as widely as possible, and have also started to move out into the greater Baltimore community and beyond. Our second annual conference, Life Sentences: The Arts and Humanities Behind Bars, took place in the Station North neighborhood, several blocks south of the Homewood campus, in the newly renovated SNF Parkway Theater, home to the Maryland Film Festival. The conference, which brought together academics, artists, and activists for three days of films, lectures, and discussion about the vital topics of prison education and reform, was also live-streamed, allowing some 25,000 people around the world to tune in. Also, in the spirit of ongoing and two-way interactions between academia and the broader public, a faculty working group on public humanities created a series of regular monthly events at a local bookstore-café we are calling Humanities in the Village, due to the name of the neighborhood abutting campus, Charles Village. After a year or so of intermittent events, we are now regularly using the space to host a humanist, either from Hopkins or elsewhere, who engages in a free-flowing conversation with the audience about a topic of his or her choosing, often with reference to a group of books curated for the occasion, which the bookstore then has on display and for sale.

As the public humanities was one of the founding missions of the Institute we’ve made a point to cast our distribution network as widely as possible, and have also started to move out into the greater Baltimore community and beyond. Our second annual conference, Life Sentences: The Arts and Humanities Behind Bars, took place in the Station North neighborhood, several blocks south of the Homewood campus, in the newly renovated SNF Parkway Theater, home to the Maryland Film Festival. The conference, which brought together academics, artists, and activists for three days of films, lectures, and discussion about the vital topics of prison education and reform, was also live-streamed, allowing some 25,000 people around the world to tune in. Also, in the spirit of ongoing and two-way interactions between academia and the broader public, a faculty working group on public humanities created a series of regular monthly events at a local bookstore-café we are calling Humanities in the Village, due to the name of the neighborhood abutting campus, Charles Village. After a year or so of intermittent events, we are now regularly using the space to host a humanist, either from Hopkins or elsewhere, who engages in a free-flowing conversation with the audience about a topic of his or her choosing, often with reference to a group of books curated for the occasion, which the bookstore then has on display and for sale.

As I mentioned before, a desire clearly expressed during the planning phase of the Institute’s development was for a program of graduate student fellowships. As of this writing we have selected and officially welcomed our third cohorts of AGHI Graduate fellows. Each fall we put out a call to current graduate students in all the humanities departments, but targeted to those who are in their fourth or fifth years, inviting them to apply for the AGHI Fellowship program. In March the faculty board reads all applications and selects a cohort for the following year. The cohort is representative of the breadth of our disciplines and methodologies, as well as the historical fields covered by our faculty; but despite this range, the students—normally in their final year of writing—replace a semester of teaching or departmentally assigned work to come together as a group and share their work with one another and members of the faculty board over bi-weekly lunch or breakfast seminars. Otherwise their only obligation is to use the time well and, ideally, to finish their dissertations!

While there’s no doubt I am biased, the AGHI seems to have filled a real need at Hopkins and is well on its way to fulfilling its mission of expanding the reach of our humanities departments and changing the external reputation of the school as exclusively a place for STEM. There have been challenges along the way, most notably the existence of the department called the Humanities Center and the understandable resistance of faculty in that department to changing a name that had long been associated with them. Most now feel, however, that the current name of that department, Comparative Thought and Literature, rather better fits what the faculty actually does and teaches, and the change has allowed for an unambiguous division of labor, not to mention active and exciting collaborations, between them and the AGHI.

For in the end that’s the real purpose of an institute like AGHI: to collaborate, to support the ideas and initiatives of the humanities faculty and students, and to enable them, and us all, to show the rest of the world the importance of what we do.