Aging is a natural process of exiting life, a process that starts at a very early age and does not end until the particular form of life expires. Although aging can be and is considered as a stable, expectable and respectable process explainable and describable, it is also an unstable, fluid, and slippery category of being that is both vulnerable and resistant to easy categorizations, especially as it leans upon the affective and emotional apparatuses of living beings. Aging as a process is bracketed by socio-political concerns and implicates varying representational modalities that demand that aging is looked at as an experience—in the hospital, the street, within systems of social injustice and incarceration, and, also in modes of its presentation in various forms of art, especially as self-presentation. The analytical gaze on aging must always be guided by the interlocking of old age and social justice.

What is, then, old age and what is social justice? What are the faces of each? What do we mean, what do we picture when we utter these words? If the words have become “terms” (as they have) can we, should we, engage in the act of de-structuring them, removing the term from the word so that term and word show independently of each other the labor that they perform in giving meaning to their referents?

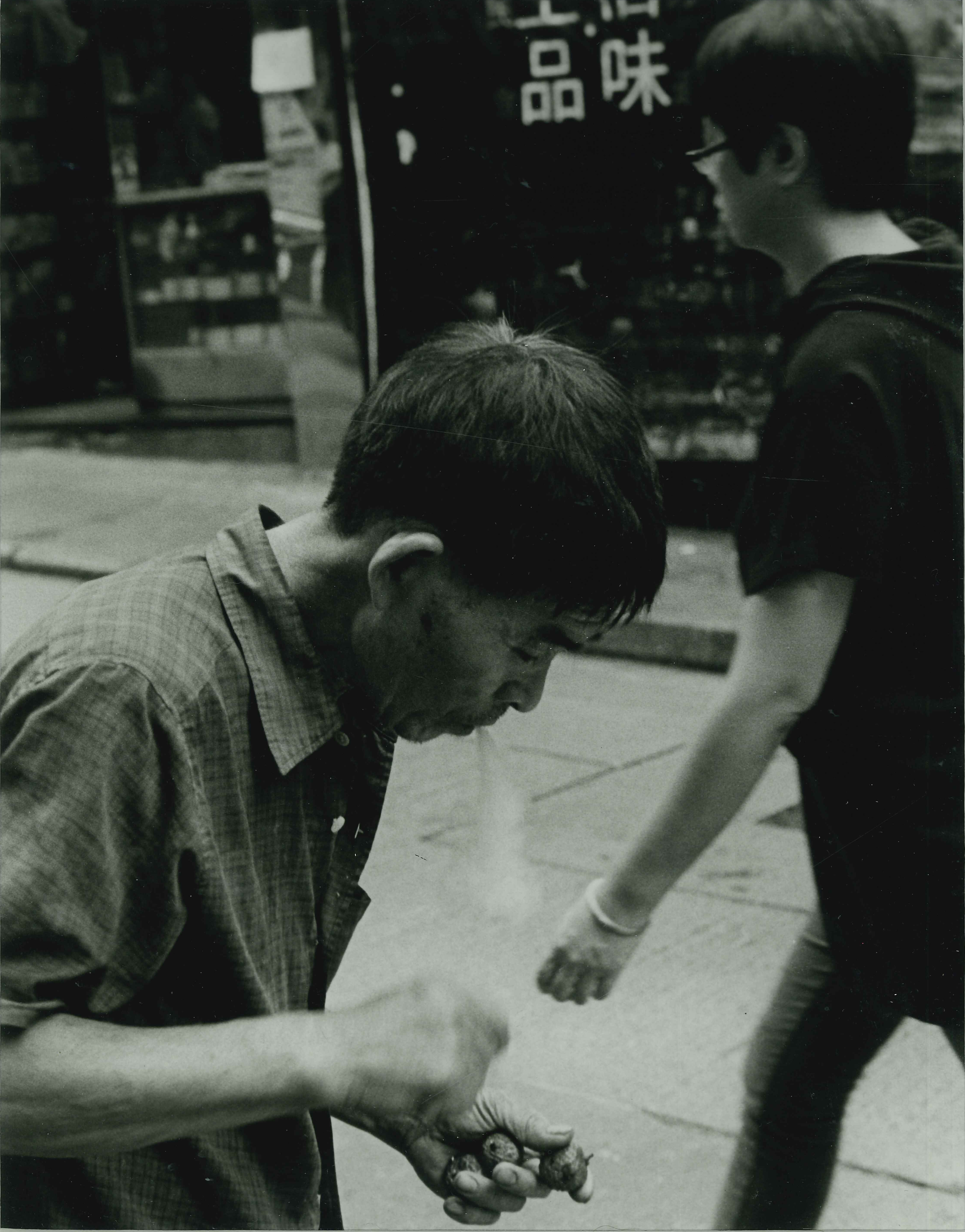

How is old age represented in art, and what cargo of meanings and significations does it carry with it? I choose to look at two photographs that index the content of inquiry into aging—one is of an old man, stooped and smoking in the streets of Hong Kong in the summer of 2014. The other one, the “Syrian Aeneas” I call it, was taken in 2016 by Yannis Behrakis at the outskirts of Eidomeni, a small town by the highway that connects Greece to Macedonia. The photograph shows a young refugee from Syria carrying his father on his shoulders to anticipated safety, a photograph eerily reminiscent of representations of Aeneas carrying his father Anchises to safety after the sack of Troy.

In 2011, as the financial crisis in Greece was raging, and the country was being accused, among other things, of threatening to bring down global capitalism, analyses abounded as to the causes of the crisis. Among accusations leveled against “the Greeks” in general, as an amorphous unibloc, no referent was more, or with more vile and bile, accused of being profligate than the pensioners. An editorial that ran in The New York Times gave as example of this profligacy a 28-year-old hairdresser in Athens who was looking forward to retirement. Everyone proclaimed that that was what had brought the country to its heels—the millions of Greeks who want to retire at the age of 50.

But let us think about what that aspiring retiree meant: a woman with a middle-school education (if that much), who had started apprenticing at a hair salon at the age of 12 or 14, initially sweeping and mopping the floor for ten hours a day, always on her feet, breathing noxious and carcinogenic fumes all day long, six days a week. From the age of 12 to the age of 50—this simple arithmetic that tells us that she will have worked for 38 years in such conditions, places both old age and social justice into the center of what any analysis of aging ought to contain.

It was precisely on that platform that we, at the Columbia University segment of the CHCI-Mellon funded project, conceptualized and designed our research, looking at “aging” as a research property of Medical Humanities.

Medical Humanities

Medical Humanities, an area of inquiry that seeks to bridge the practice of medicine with the conceptual and ethical questions that arise from the contact between medicine and its object, the human being, is inherently interdisciplinary and open to diverse and often disparate approaches to science. Moving across disciplines, lexicons, protocols, and methodologies Medical Humanities has carved a space that seeks to provide a safe discursive place for both practitioners and patients.

Before we start considering, however, the methodological and epistemological challenges posed to this new field it is imperative that we consider the field itself on two of its main parameters: first on its fundamental epistemic basis; and second, on its stated object.

Medical Humanities, as a field of study, is concerned with the challenges and difficulties inherent in the contact among human beings that occupy a number of different subject positions, that all appear to be fixed and stable which, however, upon closer consideration reveal their instabilities. These different positions are as much ontological and sociological as they are historico-political, and they all encase a power differential—these positions are, of course, the ones occupied by the different actors who find themselves entangled in such a contact, namely the physicians, other health providers (from nurses to nutritionists), intimates and family members, and, obviously the patients themselves. Although the encounter is hierarchically scripted (physicians at the very top and intimates at the very bottom) the relationality of these positions is always potentially precarious as it can be upset at any given moment when the physicians might find themselves in the position of the patient (with an entirely new horizon of socio-political and historical potentialities). In other words, from the moment that a physician will become a patient s/he engages in a relationship with the attending physicians and health care providers on a new plane of interaction. What will not change, however, is what always remains constant, which is of course the ontological position of all actors involved—they are all human beings.

As we all know, however, the definition of the human being is also notoriously slippery, a condition that renders the relationship among all these actors inherently dangerous. What we know as the “human being”, the organic being that exists as a social, political, emotional, and affective logical and dialogical entity conceptualized as apposite to the rest of nature, is being attacked constantly, as much from theory, that seeks to stretch and expand its definition to include the mechanical and the millennial, as from ideology that seeks to exclude an ever-growing number of populations, an exclusion that is racially, economically, gender, and class inflected. Therefore, if the conceptualization of the “human being” doesn’t get elasticized to the point of inclusion of the techno-being (often to the detriment of the human) it certainly gets exploded, disabled to include the poor, the migrant, the refugee, the HIV+sex worker, the black, the indigenous, following a history that has already excluded other “superfluous” and “undesirable” populations—the Jews, the leftists, women, Africans, the mentally impaired, the “Indians”, the deviants.

It is precisely at this point where medical humanities can and should intervene and interrupt. Interrupt both the epistemic and the political monologues that are erected around the notion of the human being by demanding that the interaction and contact between doctors and patients be done not on the level of the “patient” but on the level of the human being, and by challenging the monologues of sovereign power that seek to constantly define and redefine the “human being” according to the political expedience of the time.

Therefore, the epistemological and methodological questions that arise from the above statements relocate as much as destabilize the expectations regarding what constitutes the field. The primary question is, certainly, the epistemological one—what sorts of knowledges are expected and possible from this field, if we take into account the questions above. What is it that medical humanities is expecting to know, and what is it that it expects to transmit as epistemic knowledge?

The other question is methodological—how is it possible for medical humanities to produce a knowledge that will be useful and usable, unless it engenders an epistemic dialogue between medicine and the humanities and social sciences? Engaging in close readings of literature and history can certainly procure a way of reading and listening, a way of thinking on the possibility of multiple or alternative engagement with notions, concepts, and definitions. But what is direly needed is what anthropology can offer methodologically—in-depth, sustained, long term and systematic involvement with the populations present in this exchange of medicine with the humanities. An involvement that will include and translate the disparate languages and lexicons to each other, and will create the space for the cultural translation of the different positionalities.

The Columbia University Project

2013–2014

Between 2013 and 2014 the Columbia segment of the project morphed into a more comprehensive and interdisciplinary research program with a clear orientation towards splicing the question of aging onto questions and concerns of social justice, taking as point of departure the basic premises of medical humanities as a field that brings together medical practice with the social dimensions of medicine. It focused on:

- Medical humanities and social justice

- Aging and social justice comprising underprivileged aging populations: the poor, and the incarcerated.

- Long-term illness

- Intensive Care Unit populations

We actively pursued and made further contacts and collaborations with the Justice Initiative, Columbia University, and the National Research Institute (Athens) Program in Medical Humanities.

Final Project (2015–2016)

We organized two closed workshops where all of the questions and problematics posited above were addressed under the general question of aging through an in-depth exploration of specific problems.

The two workshops were each divided into into two panels, for four total segments:

2015: “Aging in the hospital, Aging in the street”

The workshop brought together engaged academics and practitioners, committed to rethinking the problems, constraints, and challenges of notions of “aging.” Sought to understand the ways aging is conceived within different physical and epistemological spaces: the clinical, the carceral, and the urban.

We opened with a clip by David Shuff, showing Alice Barker’s reaction to archival footage of her years as a chorus dancer during the Harlem Renaissance.

Panel 1: “Aging in Medicine” brought into conversation several healthcare practitioners with researchers working beyond the hospital.

- Rishi Goyal, MD, PhD (Columbia University and Columbia/New York Presbyterian Hospital) problematized the notion of “aging” as a medical category by positing the axiom that “aging is not a diagnosis.”

- Robert Sladen, MD, (Director, Columbia/New York Presbyterian Hospital SICU) examined the scale across which “fragility” is constituted among the elderly.

- Robert Cohen, MD, as a practicing primary care physician on the condition of aging patients as their health demanded new considerations.

- Adriana Garriga-López (anthropologist, Kalamazoo College, Anthropology and Sociology) on aging sex workers dealing with HIV/AIDS Puerto Rico.

Panel 2: “Aging in the Street” explored aging within the prison, the inner city, and under conditions of crisis.

- Charles Branas (University of Pennsylvania, Epidemiology) on the relationship between economic hardship, loneliness, futility, and suicide among Greece’s elderly population as a result of the financial crisis.

- Geraldine Downey (Columbia University, Psychology Dept.) on the possibilities of using a life-course development perspective to inform policy on the release of aging prisoners.

- Dr. Cohen spoke as Federal Court-appointed monitor overseeing medical care for prisoners and as Director of AIDS Center at St Vincent’s Hospital on the prison system’s aging and HIV+/AIDS population.

- Allen James (Project Manager of Cure Violence Program for the Center for Court Innovation) on the generational fragmentation of African American and Latino communities in the inner city of New York, to show how generational alienation of Blacks and Latinos in poor neighborhoods affects the distancing of youth and elderly ties.

2016: “Aging in the prison, Aging in the arts”

What is “aging,” what is “old age,” and what is “social justice”? What are the faces of each one of them? What do we mean, what do we picture, when we utter these words? The second workshop focused more closely on 1) the encounter of aging populations with art, and 2) problems of aging in specific populations. Bringing together two interdisciplinary panels the workshop opened up the discussion to the relations between aging, human rights, the arts, and social justice. To inform health as a question of social justice, the discussion revolved about how to think about the ways in which aging is being conceptualized, especially in the arts. We looked at Art that is being created by aging people, both representational and narrative.

Panel 1: “Aging in the context of incarceration and exclusion.”

- Katerina Stefatos (Columbia University, and Lehman College, CUNY) on women political prisoners and exiles before, during, and after the Greek Civil War (1946–1949) and the Colonels’ Dictatorship (1967–1974).

- Kathy Boudin (Co-director of the Justice Initiative at Columbia University) and

Laura Whitehorn (RAPP—Release Aging Prisoners from Prison) presented problems associated with mandatory long sentences that create aging populations of prisoners. - Gyda Swaney (University of Montana, Member of Salish Federation) on the challenges faced by the elderly members of American Indian nations, tribes, and federations, on and off the reservations.

- Carl Hart (Columbia University, Psychology Department) on questions faced by people-of-color who engage in drug use and explained how elderly drug users can be utilized as mentors to younger generations about the responsible use of drugs.

Steven Verney (University of New Mexico, Psychology Department, Member of the Tsimshian First Nation) had initially been scheduled to speak on his research on rates of suicide among the elderly American Indians but a last-minute conflict prevented him from joining us. Steven will join us in the publication of the volume that we are preparing.

Panel 2

A Hellenistic bust at the Berlin Museum that shows a drunken old woman is the first representation of “old age” qua old age in art, where “old age” becomes a category of its own. How is old age represented intentionally and deliberately, what does self-representation of old age look like, and what cargo of meanings and significations does it carry with it?

- Michael Friedman (Columbia, School of Social Work) talked both as an aging artist and as a social worker on art-making as a strategy for negotiating the psycho-social effects of aging.

- Ann Burack-Weiss (Columbia, Program in Narrative Medicine) on aging artists’ modified art.

- Saloni Mathur (UCLA) on the afterlife of objects as they change use where medication and medicine-connected objects become every-day objects in the life of the elderly and art material in the work of Vivan Sundaram.

- Ioannis Mylonopoulos (Columbia, Art History) spoke on representations of and positions held towards old age in ancient Greece.

Futurities

The project will go on living and expanding under the auspices of ICLS and the Heyman Center for the Humanities, as part of the Medicine, Literature, and Society project. The aging component will be in close and active interaction with the three new modules of MLS: Health as a Problem of Social Justice, BioArt, and Tropologies of Aging. The modules have been put together in collaboration with the departments of Anthropology at the New School for Social Research, Princeton University, and Cornell University. There is also a proposal for an edited volume in works which will be submitted to Columbia University Press.

Neni Panourgia is Associate Professor of Anthropology, currently teaching at the Prison Program at the Psychology Department at Columbia University. She is also the Director of the Aging and Its Tropes project at ICLS at Columbia. She is the author of Fragments of Death, Fables of Identity: An Athenian Anthropography and Dangerous Citizens: The Greek Left and the Terror of the State, among others. She publishes on critical medical studies, ethnographic theory, art and politics, spaces of exception.